Radio Set SCR-300-A War Department Technical Manual TM 11-242

[Daniel E.] Noble joined the company in early September 1940. He began by working on the possibility of adapting many of the AM systems common in that time to FM. He had no responsibility in the development of the "Handie-Talkie" radio but went to Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, with Don Mitchell to make the presentation of the unit to the Signal Corps. Among the Signal Corps officers present at that time were two, Col. Colton , and Major J. D. O'Connell, who would play important roles in the development of a longer range portable unit than the "Handie-Talkie" radio.

Sometime after the United States had gone to war, on a visit to Washington, Noble was told by Col. O'Connell that the Signal Corps had let a contract for the development of a new AM portable transmitter-receiver. Noble told him bluntly that he felt this was a grave mistake, and that the area of development should be for an FM portable unit. Noble felt strongly such a unit could be developed and that Motorola could do it. As a result of this conversation, and Noble's confidence in the company's ability to meet the challenge, Col. O'Connell issued a Signal Corps contract for the development of an FM portable transmitter-receiver to Motorola.

A series of meetings were held with Signal Corps Engineers at Fort Monmouth, and engineering meetings at Motorola were attended by Noble's team which included Henry Magnuski, Marion Bond, Lloyd Morris, and Bill Vogel. Working furiously against time, this brilliant team developed a design which included a single tuning control to tune both the transmitter and the receiver simultaneously and an automatic frequency control to insure clear communication without the need for critical precision tuning on the part of the operator. They also overcame the primary problems of establishing an adequate power supply, a minimum number of crystals, and the fungiciding of the unit to allow it to withstand tropical temperatures and humidity.

The final critical acceptance test took place at Fort Knox, Kentucky, where Col. O'Connell had set up a conference for the testing of a variety of portable and mobile communications equipment. Members of the Infantry Board, always highly critical of the application of communications equipment to battlefield conditions, had been invited as observers. Bob Galvin accompanied Dan Noble and Bill Vogel to Fort Knox for these crucial tests. Since they only had two working models, each night was spent in the hotel checking them over carefully to make sure they were ready for additional tests the following day. The performance of the SCR-300, Walkie-Talkie, during those tests, its capacity to communicate through interfering ignition noise, and the rugged quality of the design, met with unusually enthusiastic response from the hard-headed Infantry and Signal Corps officers.

Motorola was to produce nearly 50,000 of these famed SCR-300 Walkie-Talkie units during the course of the war, the first units transported by air for use in the invasion of Italy by the Allied Forces. A sizeable quantity went to the Pacific. Perhaps their greatest contribution was in the European invasion, where their role in re-establishing order at the conclusion of the Battle of the Bulge gained Motorola tremendous recognition and a general feeling that perhaps the Walkie-Talkie was the single most useful piece of communications equipment employed in the invasion.

Noble was awarded a Certificate of Merit from the Army for his part in the development of the Walkie-Talkie. Noble, accepting the award, stressed the major contributions of Magnuski, Vogel, Morris and Bond. He went on to say that the development of the Walkie-Talkie was an academic exercise compared to the contribution of the men on the battlefields, the men fighting the war.

The second source comes from A Personal Journal: 50 Years at Motorola by Andy Affrunti Sr. Privately published manuscript, 1985, p. 63-64:

Soon after I started in the research lab in late 1940, Henry Magnuski and I received our first assignmment based on a military contract: a portable FM communications radio. It was a typical Monday morning when Dan Noble approached Henry and me and asked both of us to sit at my workbench. Dan motioned Henry to sit at his right and me at his left and placed an official looking sheet of paper on the bench. I noticed the fancy heading that read, United States Army Signal Corps. Dan read the eight paragraphed items aloud and finished by saying, "Henry and Andy, I want you to start working on this immediately. During my visit to the Signal Corps last week they placed a life-and-death priority on this program for the infantry. You will get whatever assistance you need and I expect to see a prototype fabricated as soon as possible."

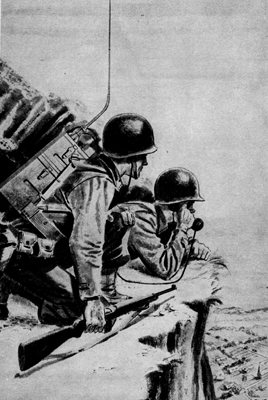

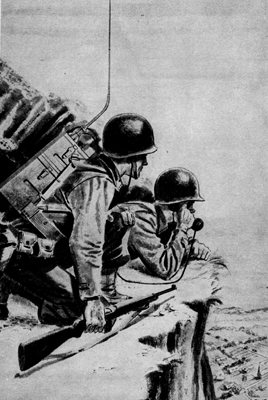

Shocked by the demand he placed on us, we read and reread this one sheet of paper several times. The Signal Corps designated this communications equipment as a portable infantry battalion transceiver nomenclatured SCR-300. We soon realized that this was a specification document to design and develop a portable, frequecy modulated radio receiver and transmitter powered by batteries. The complete equipment should not weigh over 35 pounds and be carried on the back of an infantry combat soldier. It should provide solid communications over a distance of three miles and be water-proofed against rain. No more than two crystals could be used and it should cover a frequency range continouously variable from 40.0 to 48.0 megacycles providing 48 channels of communications.

Continuing on p. 73-74:

We tested and retested our prototype in the lab and finally just a few days before the Signal Corps representatives came, Henry and I were ready. We stood eight miles apart - more than twice the specification - on a bright spring day in 1941, he standing on the flat roof of the Tropic-aire building next to the Augusta Boulevard plant, I in the Thatcher Woods Forest Preserve parking lot to the west of the plant. Marconi or Bell couldnt have felt better when they heard others on radio or telephone than I did when I heard Henry's Polish-accented voice from Augusta Boulevard: "Ondy, do you hear me?"

"Yes, Henry," I said from my forest preserve station, "I hear you very good, loud and clear."

When we reported to Dan Noble and our lab associates the successful result of our test, everyone was jubilant. Our prototypes housed in the two green wooden boxes took on an aire of great importance. A week later in the same location the field test was repeated for Signal Corps officials who gave us a quick verbal approval to develop a production prototype.

The following links are the fully scanned contents of the SCR-300-A Technical Manual.

Page 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

Page 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37

Page 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52

Page 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65

Page 66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

Page 100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

Page 130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

Page 160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

Figure-88

Addenda-1 Addenda-2 Equipment-Report

Files in TIF Format

Copyright © 2005 H. S. Magnuski

Updated 2005-07-09 hankm@mtinet.com